- WILLKOMMEN

- DISCOVER GERMANY

- GEOGRAPHY OF GERMANY

- HISTORY OF GERMANY

- Timeline of German History

- The Hanseatic League

- The German Confederation

- The Hambach Festival

- The German Revolution of 1848/49

- The North German Confederation

- The German Empire

- Otto von Bismarck

- German Colonies

- World War 1

- The Weimar Republic

- National Socialism

- World War 2

- Zero Hour

- West Germany

- German Democratic Republic

- German Reunification

- LAND AND PEOPLE

- GERMANY'S SYMBOLS AND SLOGANS

- GERMAN CITIES

- CLIMATE OF GERMANY

- VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE

- SPORTS IN GERMANY

- POLITICAL SYSTEM

- GERMAN LITERATURE

- GERMAN MUSIC

- ENTDECKE DIE USA

- GEOGRAPHIE DER USA

- GESCHICHTE DER USA

- Chronologischer Abriss der Amerikanischen Geschichte

- Die 13 Kolonien

- Die amerikanische Revolution (1775-83)

- Amerikanisch-Tripolitanischer Krieg

- Die Junge Republik

- Lewis und Clark Expedition

- Westexpansion

- Krieg von 1812

- Monroe Doktrin (1823)

- Mexikanisch-Amerikanischer Krieg

- Transkontinentale Eisenbahn

- Der amerikanische Bürgerkrieg

- Die Rekonstruktion der Republik

- Spanisch-Amerikanischer Krieg (1898)

- Die USA im I.Weltkrieg

- Great Depression

- Die USA im II.Weltkrieg

- 11. September

- Geschichte der Bürgerrechte

- LAND UND LEUTE

- SYMBOLE UND SLOGANS DER USA

- STÄDTE DER USA

- KLIMA DER USA

- SPORT IN DEN USA

- FLORA&FAUNA

- POLITISCHES SYSTEM

- LITERATUR DER USA

- Epochen der amerikanischen Literatur

- Kurzportraits

- William Bradford

- James Fenimore Cooper

- Frederick Douglass

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

- William Faulkner

- Francis Scott Fitzgerald

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Ernest Hemingway

- Washington Irving

- Emma Lazarus

- Herman Melville

- Edgar Allan Poe

- John Steinbeck

- Henry David Thoreau

- Mark Twain

- Booker T. Washington

- Walt Whitman

- John Winthrop

- US-MUSIK

- GUIDE

OVERVIEW

The German Empire was founded in 1871 after the unification of several German-speaking states under the leadership of Prussia's Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The German Empire was a major European power, with a rapidly growing economy and a strong military. It also had a significant cultural impact on the world, with many famous writers, philosophers, and scientists hailing from Germany during this time.

KEY POINTS:

- The German Empire was established on January 1, 1871

- Wilhelm I was proclaimed German emperor in the Halls of Mirrors in Versailles on January 18, 1871

- Germany was unified with "Blood and Iron"

- The working class benefited because of Bismarck's social securities

- The German Empire was characterized by militarism and science

The German Empire was established in 1871 after a series of wars known as the Wars of German Unification. Otto von Bismarck, the Chancellor of Prussia, led these wars, which started in 1864 with the First Unification War against Denmark. After Denmark's defeat, Prussia and Austria acquired the northern states of Schleswig and Holstein, but Austria was left with no significant seaport as Holstein was an enclave connected to Prussia. This led to the Second Unification War between Prussia and Austria in 1866, which ended with Austria's defeat and the formation of the North German Confederation. The Confederation paved the way for the establishment of the German Empire, without Austria's rivalry.

In 1870, the Third Unification War took place, which was fought against France. The North German Confederation's victory was possible due to Bismarck's strategic alliances with the southern German states. The Third War was significant as it united Germany as a nation and resulted in the German Empire's establishment on January 1, 1871, with the introduction of a new constitution. On January 18, 1871, Wilhelm I was proclaimed the German emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

The German Empire was a constitutional state that consisted of 22 individual states and three Free Cities, and had a total population of around 40 million citizens. The executive branch of the German Empire was composed of the emperor and the Bundesrat, which represented all 25 federal states and had the power to declare war and peace. The Bundestag and the Chancellor were the other two political entities that governed the German Empire.

Otto von Bismarck was the most important and influential Chancellor of the German Empire. He served as Chancellor under the Empire's banner, and was one of eight officeholders who held the position during its existence.

Otto von Bismarck served as a Prussian Prime Minister and State Secretary from 1862 onwards. Wilhelm I wanted to strengthen the Prussian army, but faced opposition from liberal forces who used the Prussian constitution to block the reform. Bismarck argued that state business needed to continue, even if it meant bypassing parliament. He found a gap in the constitution and used it to push through the military reform. Bismarck also emphasized the importance of the military's virtues, claiming they could enrich daily life and society. He famously declared that Prussia's destiny in Germany would be decided by "blood and iron," which initially met with resistance from liberal forces but gained support after the victory against Austria.

The North German Confederation paved the way for German unity, and in 1870, Bismarck used alliances with southern German states and good relations with Russia to launch a policy stroke against France. The final War of German Unification was initiated by France, and the victory of Sedan set the stage for Germany's triumph. Emperor Napoleon III, along with 100,000 French soldiers, was captured by German forces. On January 18, 1871, the German Empire was proclaimed in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles (although officially, it was established on January 1 by constitution). Wilhelm II was crowned German emperor, and Bismarck became chancellor of the German Reich and a national hero. The German military's success not only led to celebration but also served as a model for a German way of life.

Bismarck's domestic policy was characterized by several undertakings to unify the majority of the Reich's citizens. Some groups, namely the Catholics and the socialists, were considered enemies of the Empire. Bismarck demanded that the first group should obey the Emperor only instead of the Pope. The socialists, however, were considered enemies because they influenced labor. The socialist's agenda often stood in stark contrast to Bismarck's goals, namely a state in which the Emperor, the aristocracy, the chancellor, and a selected group from the upper-class should be in charge of political affairs. Bismarck passed a series of laws or social securities (Sozialgesetze) for the working class's profit to prevent the socialist's increasing power. These achievements that had a substantial impact on daily life are still in place in today's Germany. The Sozialgesetze included health and disability insurance for the working force and a pension as well as a dependent's pension. His contentions with Catholics became known as the Kulturkampf, which aimed to limit the Catholic Church's political and social influence in Germany and resulted in the separation of religion and government.

Otto von Bismarck, the Chancellor of the German Empire, wanted to reassure neighboring states that the unified Empire posed no threat to them. He declared that the Empire was saturated, indicating that they had no expansionist intentions. However, the French were still determined to reclaim Alsace-Lorraine from the Germans, and they formed alliances accordingly. Although they attempted to offer parts of their territories in Indo-China in return for Alsace-Lorraine, the effort was unsuccessful. Bismarck's strategy was to maintain good relations with Russia to prevent any possible conflicts with France.

Bismarck was skeptical about acquiring German colonies for two reasons. Firstly, he knew that establishing colonies would be very costly. Secondly, he did not want to interfere with any British plans. However, private interest groups were growing rapidly, and other European powers were already acquiring new continents. Additionally, overseas territories offered benefits such as new markets for goods and raw materials. Therefore, Bismarck promised his fellow citizens a German Empire that focused on the positive aspects of colonization.

The German Empire was at the forefront of technological progress during the industrialization era. One of the most visible symbols of mobility and progression was the widespread use of tramways in major cities. The German engineers demonstrated their expertise in the development of automobiles as well. The first car that ever drove on the roads of Mannheim, Germany was a remarkable achievement of German engineering. It was designed by Carl Benz, who had already established a company for gas engines in 1883. This first automobile was a significant milestone in the history of technology, and it opened up a new era of personal transportation. Mannheim, the birthplace of the automobile, became a hub of innovation and a flourishing business location, with many related industries and services thriving there. The development of the automobile industry had a profound impact on the German Empire, and it paved the way for a new age of transportation and technological advancement.

The German Empire was a period of great scientific and technological progress, with many significant discoveries made during this time. One of the most notable scientific achievements of the era was the development of the theory of relativity by Albert Einstein. This groundbreaking theory revolutionized the field of physics and helped to shape our understanding of the universe. Other notable German scientists of the time include Max Planck, who is credited with the development of quantum theory, and Robert Koch, who made significant advances in the study of infectious diseases. Koch's discoveries helped to establish the field of microbiology and led to the development of new treatments for diseases such as tuberculosis.

One of the most significant and world-changing discoveries of this era was the discovery of X-rays. Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen, a German physicist, discovered X-rays in 1895 while experimenting with cathode rays. He noticed that a fluorescent screen he had placed near a cathode-ray tube started to glow even when it was not in direct contact with the tube. He soon realized that a new type of ray was responsible for this glow. Roentgen's discovery in Würzburg led to a revolution in medicine and the development of X-ray machines, which allowed doctors to see inside the human body without surgery. The discovery of X-rays also won Roentgen the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901.

Scientists and researchers made groundbreaking discoveries in areas such as chemistry, physics, and biology. In chemistry, scientists such as Emil Fischer made significant contributions to our understanding of the molecular structure of organic compounds. In addition to these scientific breakthroughs, the German Empire was also a time of great technological progress. The development of the diesel engine by Rudolf Diesel in 1892 was a major advancement in the field of engine technology, with the diesel engine quickly becoming a popular choice for powering everything from ships to trains.

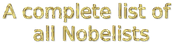

21 Nobelists emerged from the German Reich. Seven of them received a Nobel Prize in chemistry, and six received a Nobel Prize in physics, including Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and Max Planck. Robert Koch was awarded for his discovery of tuberculosis germs, and Emil von Behring was awarded for his vaccination achievements.

| 1901 |

Emil von Behring, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen |

| 1902 | Emil Fischer, Theodor Mommsen, |

| 1905 | Adolf von Baeyer, Robert Koch, Philipp von Lennard |

| 1907 | Eduard Buchner |

| 1908 | Paul Ehrlich, Rudolf Eucken |

| 1909 | Ferdinand Braun, Wilhelm Oswald |

| 1910 | Paul Heyse, Albrecht Kossel, Otto Wallach |

| 1911 | Wilhelm Wien |

| 1912 | Gerhart Hauptmann |

| 1914 | Max von Laue |

| 1915 | Richard Willstätter |

| 1918 | Fritz Haber, Max Planck |

The military played a significant role in the German Empire. Under the leadership of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the Prussian army was expanded and modernized, becoming one of the most formidable fighting forces in Europe.

The German military was divided into two main branches: the army and the navy. The army was composed of conscripted soldiers, while the navy was composed of volunteers. The army was known for its discipline and professionalism, and it became the backbone of the German Empire's military might.

One of the key reforms introduced by Bismarck was the introduction of universal conscription. Every male citizen between the ages of 17 and 45 was required to serve in the army for a period of two or three years. This system ensured that the army was constantly being replenished with fresh recruits, and it helped to foster a sense of patriotism and loyalty to the state among the population.

In addition to universal conscription, Bismarck also introduced a number of other reforms aimed at modernizing the army. He increased the size of the standing army, improved training and equipment, and introduced new weapons and tactics.

The German military continued to be one of the most powerful in the world up until the outbreak of World War I. Its innovations and reforms helped to establish the German Empire as a major player on the world stage, and its legacy is still felt today in the modern German military.

Sources / Quellenangabe:

Kitchen, Martin. A History of Modern Germany. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Naumann, Günter. Deutsche Geschichte. Wiesbaden: marixverlag, 2018.